|

Francis Washburn and the California Hundred were as distant and different as

Boston and San Francisco. Washburn was a blueblooded Boston Brahmin. He

was as close to American aristocracy as it gets. The impetuous,

free-spirited men of the Hundred were… not. Yet over time, Washburn

and the Californians developed a high respect for each other.

Washburn came to the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry with some serious

military experience. He had already learned the hard realities of combat

and military life with the 1st Mass. Cavalry. He enlisted in

this well-connected regiment in 1861 as a 21-year-old shavetail

lieutenant from Harvard University’s Lawrence Scientific School. When

the 2nd Mass. Cavalry was organized, he accepted the

captaincy of Company D (Massachusetts men, of course). After all,

promotion is good.

By in large, the Californians held their highbrow Bay State officers in low

regard. But time and service together helped close the gap. When Captain

James Sewell Reed, commander of the California Hundred, rose to the

command of the first battalion in August, 1863, Washburn took command of

Company A. One of his men, Thomas Barnstead, reported to a California

newspaper, “a Massachusetts man, is now our Captain, and, so far, is

liked very well.” Others felt the same about Washburn. One of the

Massachusetts officers recalled that Washburn, “proved one of the best

officers of the line.” In camp, he exercised a level of fairness that

struck home with the Californians. In the field, he led from the front.

Enough said.

In February 1864, opportunity reached out again. Washburn was

mustered in as lieutenant colonel of another new regiment — the 4th

Massachusetts Cavalry. A year later, Washburn was promoted full colonel.

His regiment was part of the Army of the Potomac’s stranglehold on

Petersburg and Richmond when Lee abandoned his fortifications in a last,

desperate move to save his army. Washburn was sent with a force of

cavalry and infantry on April 6, 1865 to destroy the bridge at High

Bridge, Virginia before the enemy could escape across it. The union

troops reached the bridge just as the confederates did.

In an impetuous charge, Washburn and less than 100 cavalrymen,

backed by 800 infantrymen, took the bridge and cut their way right into

the main force of the Army of Northern Virginia. Hundreds of confederate horsemen swarmed into the

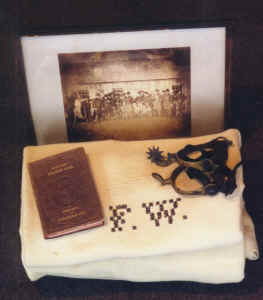

melee. According to family history, the rowel of one of his spurs was

snapped off by a bullet or canister ball during the charge.

In the swirling, hand-to-hand combat, Washburn became engaged in a saber

duel with confederate Brigadier General James Dearing. This personal

clash was cut short when Washburn was shot through the cheek by a rebel

cavalryman. Falling from his horse, he then received a severe saber blow

to his skull. It was over. The twice-wounded colonel was brought back to

friendly lines. Most of the other surviving yanks were captured. The

outnumbered federals lost heavily and were unable to destroy the bridge.

But as a result of their audacious assault, Lee expected a larger force

behind them. So he halted his advance, giving time for the 24th

Corps to cut off the confederate retreat.

Washburn was mortally wounded. A brevet brigadier general’s

commission was rushed through channels, based on his recent gallantry.

He held on to life through Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. And through

Lincoln’s assassination. He held on through the long, painful,

jouncing, bouncing, journey to his brother’s home in Worcester. But

the young, tall, delirious, dying, strikingly handsome, horribly maimed

and unquestionably brave Francis Washburn finally, mercifully died of

his wounds on April 22, 1865. His connections to the California Hundred,

the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry and all others were now

history.

###

Image

and text courtesy of Richard K. Tibbals

|